Guides are typically laid out in a grid configuration of some sort or sectioned into multiple tables by a category or step of a process. On top of that not all guides are created equal, many technically qualify as guides, but lack substance. If someone has to visually bop around your guide to find what they are looking for, the guide does not pass the layout test. The layout or structure of a guide must be that so, when someone is trying to find/reference information from the guide, they can do so logically or simply. It takes both content and layout to make something a guide. Guides are reference materials, how-tos, and/or comparison tables.

Pixar rules of storytelling how to#

For example, "A cool guide about identifying poison ivy", "A cool guide showing how to clean your house", or "A cool guide for painting your living room". #22: What’s the essence of your story? Most economical telling of it? If you know that, you can build out from there.To help keep things nice, searchable, and maintainable, all posts must be prefixed with "A cool guide". #21: You gotta identify with your situation/characters, can’t just write ‘cool’. How d’you rearrange them into what you DO like?

Pixar rules of storytelling movie#

#20: Exercise: take the building blocks of a movie you dislike. #19: Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.

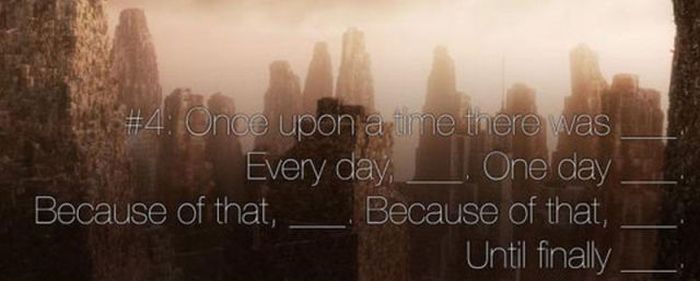

#18: You have to know yourself: the difference between doing your best & fussing. If it’s not working, let go and move on – it’ll come back around to be useful later. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against. #16: What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. #15: If you were your character, in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations. #14: Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience. And the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th – get the obvious out of the way. #12: Discount the 1st thing that comes to mind. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone. #11: Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. What you like in them is a part of you you’ve got to recognize it before you can use it. Lots of times the material to get you unstuck will show up. #9: When you’re stuck, make a list of what WOULDN’T happen next. In an ideal world you have both, but move on. #8: Finish your story, let go even if it’s not perfect.

Endings are hard, get yours working up front. #7: Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle.

#6: What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. You’ll feel like you’re losing valuable stuff but it sets you free. #3: Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about til you’re at the end of it. #2: You gotta keep in mind what’s interesting to you as an audience, not what’s fun to do as a writer. #1: You admire a character for trying more than for their successes. Stephan Bugaj’s analysis is really in-depth and amazing – it’s a worthwhile read to better contextualize the rules. They are more to be used as bits of advice to use when needed or as you see fit.

These aren’t necessarily a formula for writing, in fact you don’t even need to use all of them. And of course, one can follow the originator of the tweets, Emma Coats on her blog about her career in story boarding. You’ll find several different sources including Open Culture, Aerogramme Writer’s Studio, and even a super-deep analysis by Stephan Vladmir Bugaj. If you haven’t already heard of Emma Coats’ famous tweets regarding storytelling rules she’s learned during her Story Artist days at Pixar, you should definitely do an online search for it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)